Growing up in Memphis, Chantel Barcenas, 18, considered herself an all-American Girl until she got a rude awakening one day in high school: She wasn’t a United States citizen at all; she was a Mexican citizen—if only in name.

When the freshman Christian Brothers University business major started considering going to college as a Cordova High School student, getting a Tennessee driver’s license or traveling out of the country, it really hit her what lack of citizenship meant, because she could do none of those things.

She felt lost.

“I kind of lost identity for a while because of the whole political issue of me being undocumented,” said Barcenas, who was born in Monterrey, Mexico, and brought to Memphis when she was 1 year old. She committed her conflicted feelings to poetry: “Feeling American in July/Yet feeling Mexican in September/but I’m never enough of either.”

Barcenas’ saving grace proved to be a 2012 Obama-era executive order called the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which allowed children brought here by their undocumented parents to qualify for a temporary reprieve with the option to renew. DACA, as the policy is known, was a last-ditch effort by President Barack Obama after years of Congress being unable come together and pass a range of comprehensive immigration reform plans. The idea behind DACA is that children, called Dreamers, many of whom were too young to recall ever crossing the border legally or otherwise, shouldn’t be forced to leave the only country they’ve ever known.

Barcenas’ parents rejoiced at their daughter’s second chance, she said. Really, all they ever wanted was for their children to have access to opportunity — which is why they came to the States, even though they couldn’t speak the language. But as they cheered their daughter’s opportunities through DACA, they also mourned because her older brother, Karim Pluma, had just returned to Mexico less than a year before the executive order was issued.

“He went back because he didn’t have a Social Security number or any documentation, and although he got accepted to school here, we couldn’t afford it because tuition would be twice as much if you’re undocumented,” Barcenas said.

Barcenas knows other DACA recipients who got accepted to college but couldn’t afford it because they would have to pay out-of-state tuition. Barcenas was able to go to CBU thanks a scholarship from Dream.Us, a nonprofit group that provides awards so undocumented students can pay for college, including DACA recipients, who cannot get federal aid. She also works part-time in retail, thanks to the work permit DACA provides.

Like so many others, Barcenas’ family pulled together the initial $465 DACA application fee (which later rose to $495, a fee owed every two years if the recipient opts to renew) so she could stay, pursue higher education and the dream of, well, doing whatever her young mind could conjure.

In September, when U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the end of the DACA program, the Barcenas family peace was yet again broken. Now, 800,000 DACA recipients nationwide face deportation, and 3,000 of them living in Memphis face uncertain futures as strangers in strange lands.

“I had a breakdown, I started crying, my parents started gathering their stuff up. My mom was getting rid of stuff; she was already making Plan B, C and D,” Barcenas recalled. “It’s still a question mark, why is this still happening? I felt devastated, numb, very confused; there were so many mixed emotions.”

Before the government stopped accepting DACA renewals, Barcenas said some students asked her what they needed to do. Helping others kept her mind off her own situation, which likely won’t change unless Congress does something first.

“I unfortunately don’t get to renew,” Barcenas said. “Mine expires next September.”

Based on the White House’s recent immigration policy decisions, the future looks bleak. For example, the Trump administration has decided to end Haitians’ Temporary Protected Status and send them back home in 18 months. Many Haitians came to the States in 2010 after an earthquake decimated the country, which is struggling to rebuild. Advocates say not enough jobs nor housing exist to absorb an influx of 50,000 Haitian citizens. And, like the DACA recipients, those Haitian citizens now have children who are Americans, and they own property and have jobs they’d be forced to relinquish.

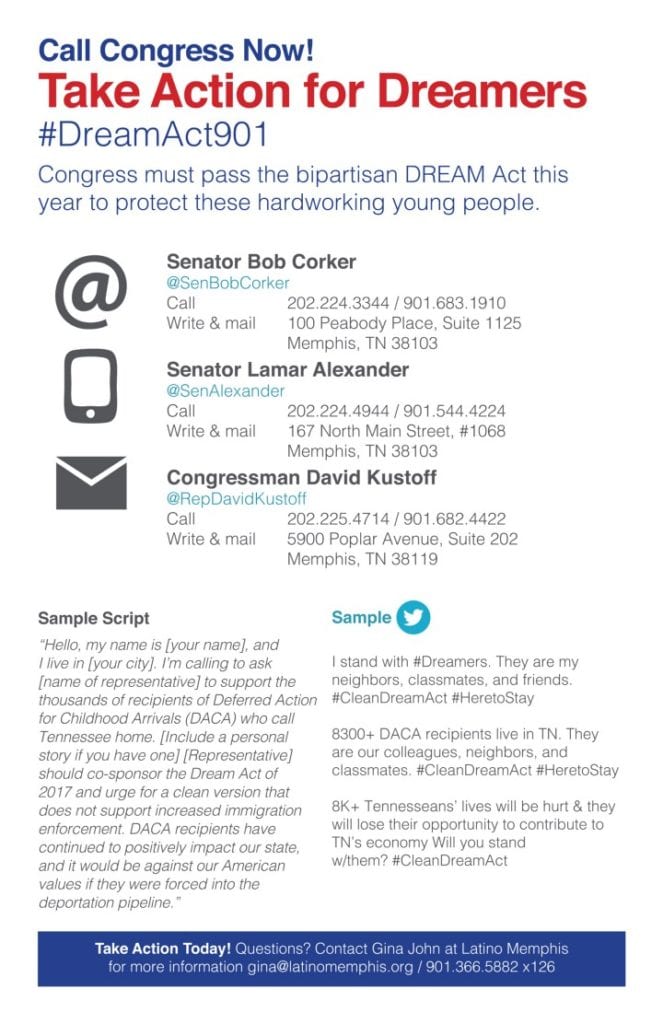

The Republican-sponsored RAISE Act seeks to rejigger the immigration system by prioritizing those with special skills who can get H1B visas to work in American companies, and deprecate those with family ties or who need refugee/asylum status. Meanwhile, Congressional representatives from Tennessee, like Senator Bob Corker, Senator Lamar Alexander and Rep. David Kustoff, haven’t even gone on the record with their opinions on the fate of DACA recipients here.

Despite her current situation, Barcenas proudly considers herself part of both cultures because while she grew up here honoring American traditions and holidays, her parents always spoke Spanish at home and celebrated certain Mexican holidays, such as Día de Los Reyes (Three Kings Day), which tethered her to those roots.

“Even when I see both flags, I’ll feel very prideful,” Barcenas said.

Barcenas has used her experience to help others by participating in an immigration support group at CBU, Dreamers United, and interning at Latino Memphis, a nonprofit advocacy organization where she met fellow DACA recipient David Aguilar, a senior at LeMoyne-Owen College. Being at that nonprofit helped alleviate some of her fears because she met others in the same situation.

“The DACA program allowed young people like Chantel the ability to drive, work and live without the fear of deportation in a country they call home,” said Gina John, advocacy coordinator at Latino Memphis. “Without it, they will lose all those provisions and be at risk of being forcibly separated from their families and return to countries that they do not know.

“Through DACA,” John continued, “Chantel has been a light to others in a similar situation by sharing her story at numerous events and standing up for herself and others who want to continue to actively contribute to their communities.”

Wherever she lands, Barcenas wants to work in the nonprofit world or for a nongovernment organization that helps people help themselves.

Meanwhile, she continues to discuss the future of Dreamers by reciting poetry, speaking at public events on DACA and just sharing her story with others.

“I feel like it’s very important,” Barcenas said, “to get that message across to others who maybe don’t know what exactly our struggles are like.”

What’s next?

If you’d like to advocate on behalf of DACA recipients, your best best is to contact Rep. David Kustoff (R-8th) and Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-TN) and Bob Corker (R-TN).

- Democracy.io offers an easy tool for identifying congresspersons and writing them in one fell swoop to save you time.

- Facebook has a Town Hall feature, which will tell you who your representatives are and allow you to follow them, so you know what they’re up to. You may turn on a constituent badge for commenting, so your representative knows they’re working on your behalf. You may also turn on reminders for voting in your district and town halls because you showing up is part of getting things done.

- Print and send a postcard, created by Latino Memphis, to federal representatives.

This article first appeared on MLK50: Justice Through Journalism.