For the past several weeks, cities across the country have seen a multitude of protests and acts of civil disobedience following announcements that police officers would not be indicted in the murders of two unarmed Black men, Michael Brown, Jr. in Ferguson, MO, and Eric Garner in New York City. Thousands of protesters have hit the streets. Interstates, highways, and shopping malls have been shut down. Televised events have been disrupted. A number of high profile athletes and celebrities have spoken out in solidarity. People are not only expressing their anger, but affirming the value of Black life.

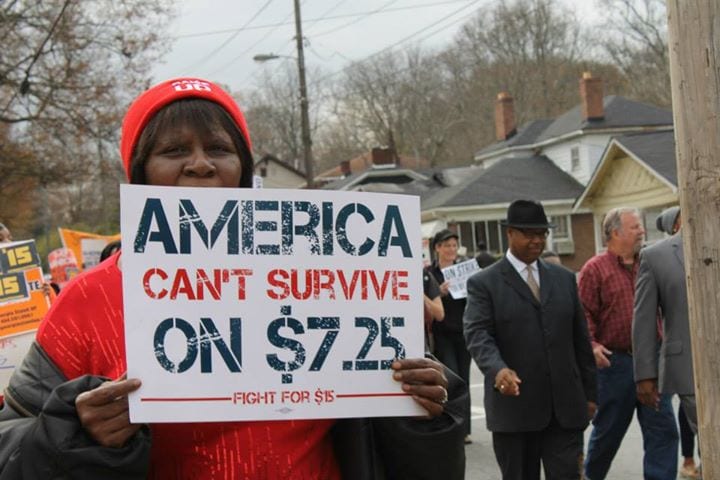

In the midst of this fervor, on Thursday, December 4, fast food workers around the country went on strike. There were protests in 190 cities—a record number since the Fight for 15 movement started two years ago. The protests in Atlanta followed previous actions this year, including a series of actions in September. This time, as the atmosphere in Black and low-income communities in the country has been affected by mass protest, the strikes were also different.

Of the approximately 50 protesters gathered outside of KFC on the corner of Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. and Joseph E. Lowery Blvd in Atlanta’s West End, many were people who worked in sectors that had not previously joined the protest. Organizers with ATL Raise Up, one of the groups that anchored the strikes, explained that people who worked in convenience store and airports had joined the fight for a minimum wage increase. In fact, after rallying at the KFC for an hour, protesters marched down Lowery Blvd to join workers at the Family Dollar on the corner of Lowery and Joseph E. Boone Blvd.

Community support was strong in this predominantly Black neighborhood. Drivers passing by the busy intersection honked in solidarity. Students from the Atlanta University Center, home of the city’s historically Black colleges, members of the Concerned Black Clergy, and other members of the community joined the protest. Notably, the group was joined by State Representative Tyrone Brooks, who announced that he and Representative Dewey McClain had pre-filed legislation to raise the minimum wage.

Though the mostly Black crowd was focused on labor issues, it was clear that the action could not be completely separated from the protests against police violence. Chants for “$15 and a Union” were followed by chants proclaiming that “Workers Lives Matter,” an extrapolation from the “Black Lives Matter” chant developed by Black women activists after the murder of Trayvon Martin that has been used widely since August. At one point, protesters and community members joined together chanting, “Hands up, don’t shoot!”

As the protesters marched down Lowery, they were accompanied by multiple police vehicles. When they arrived at the Family Dollar in impoverished Vine City, they were met by an Atlanta Police Department prisoner transport van along with additional police cars. One area resident walking up to join the protest approached an officer yelling, “I have my hands up! I have my hands up!”

The connection to anti-police violence protests was largely organic, and seemingly inevitable. The disproportionate police presence at the action only served to increase the connection and empower the crowd. Indeed, making the connection is part and parcel of what makes “Black Lives Matter” such an important rallying cry: If Black lives truly matter, then improving the quality of Black lives by paying working families a living wage is imperative.