“Gary is a rising sun. Together, we shall beat a way; together, we shall turn darkness into light, despair into hope and promise into progress. For God’s sake, for Gary’s sake — let’s get ourselves together.” — Richard Hatcher’s inauguration, Jan. 1, 1968

“The potential for change in Gary exists, if allowed to happen.” — the last sentence in a 2014 report about Gary by the Federal Reserve of Chicago Industrial Cities Initiative.

With dollars signs in their eyes, the new president and the old Congress are talking infrastructure. In his campaign literature, President Trump signaled that he would spend at least $1 trillion over the next 10 years. He’s already looking at 50 projects he wants to get a move on right now. (Cagey Washington observer Al Hunt has an illuminating column on the White House’s strategy — including the potential to win over African American voters.)

The Senate Democrats are pitching a plan that they say will, for same price, create 15 million jobs.

The work is overdue, but the numbers being touted aren’t nearly enough, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.

How we pay for it is important.

My mind is on who gets to work on these projects.

When I hear infrastructure, I think of the general good, I think of jobs, and I think of Gary.

Gary, Indiana.

Its last 50 years tells us about where are as a people — fractured and susceptible to influences beyond our control.

Gary elicits derisive snickers about blight and black folks. Last January, the Economic Innovation Group reported Gary was the third most distressed city in the nation based on resident income, poverty and joblessness. Only Camden, N.J. and Cleveland were ranked higher. Gary is nearly 90 percent African American.

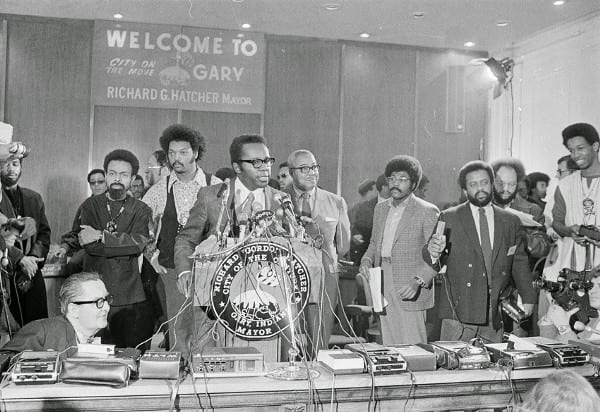

History shows that racism was at the heart of Gary’s downward spiral. It began after the 1967 election of Richard G. Hatcher, the city’s first black mayor and the first African American elected mayor of a U.S. city with a population of more than 100,000.

In the half century since, Gary’s citizens have been victimized by the collapse of the steel industry and its automated-driven recovery; a contentious and sometimes treacherous relationship with regional politicos and the state government in Indianapolis; a wave of white flight that led to a friendly deal to create a new city to capsize Gary; and political in-fighting and crooked politicians.

In the trips I took to Gary last year to see, to listen, to ponder, I came to the realization that Gary was not just the avatar for the decline of U.S. industrial might or, for critics, the failed promise of black leadership.

Gary is emblematic of the hyper-invisibility that stigmatizes the African American community: the absence of knowledge; the imagined, often wrong-headed assumptions.

The mere mention of me driving to Gary brought on worried expressions and comments such as “You need to be really careful,” as if I were flying to Syria, instead of northwest Indiana.

The anger of Gary’s residents is an outgrowth of what happens when political and economic institutions dominated by white faces and hands exempt themselves from the mess they or their forefathers helped create.

Confirming the obvious highlights what generational racism does to people. Gary is the locus of the region’s Black Lives Matter protests. No longer solely a movement around police brutality, local activists have galvanized around economic justice and immigration reform.

The unemployment rate is more than twice the national average; the city’s median income is nearly 50 percent lower than the national median. More than a quarter of the city’s residents live at or below the poverty rate. Nearly half the city’s residents are renters.

With Indiana’s property taxes capped at 1 percent, Gary has been in austerity mode for years.

The city’s population was at 189,000 in 1960; today it’s at 86,000.

But Gary’s future is so promising that even the Chicago Federal Reserve reported on the city’s valuable assets — its proximity to Chicago, an airport with an expanded runway to meet FAA guidelines, lake access and recreation, rail and highway systems, and home to a campus of Indiana University.

The Fed writers quipped “there is almost no way not to make it better.”

Of course there is a way to jack this up — and it’s been going on for a half century.

As the Chicago Fed notes, the drawback to growth has been the lingering history of racial tension.

There is no dispute that the rebirth of Gary wrests on revitalizing and developing its assets. Interference is what drives the fear among residents, including Hatcher.

Last March, Hatcher sat in the front pew of Gary’s Trinity United Church of Christ at a candidate forum for local and state-wide offices. Each candidate acknowledged his presence, more than a few paid homage with praise for his tenacity and intellect.

Hatcher’s intellectual and political credentials were impeccable. He grew up in Michigan City, Ind., graduated from Indiana University with honors and received his law degree from Valparaiso University School of Law in 1959.

Hatcher was deputy prosecutor for Lake County, and elected to the Gary city council in 1963. He’s the only first-term councilman to be selected as council president.

Hatcher’s ascent is the quintessential American story.

With deference to Jonathon Kozol, America is about savage inequalities.

White flight began before Hatcher’s mayoral triumph, but picked up the pace afterward.

The official story is that in 1971 the people of Ross Township voted to create the city of Merrillville. However, it’s not that clean.

The cruelest stroke, Hatcher has noted, was how local, white Democrats in Lake County and Republicans in Indianapolis pushed specifically worded legislation to skirt the state’s buffer zone for cities, thus the creation of Merrillville, just to the south of Gary.

Merrillville sucked the retail base and cultural institutions out of Gary.

In the early 1970s, Hatcher drove to Chicago’s Sears Tower to meet with the retailers executives. They were moving from downtown Gary to Merrillville. When he probed, Hatcher was told that the Gary store was one of the most profitable sites in the region. So why close it? Merrillville was a long-term move — even then, Sears could see what the future held for Gary, and it wasn’t growth.

History like this can’t be erased, and new ideas and institutions are automatically suspected to be another scheme to drain more out of Gary.

The creation of the Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority is an example. It isn’t inherently a bad idea. But given the amenity between the city and the state, it’s easy to see why there is mistrust.

Implemented in 2005 by then Gov. Mitch Daniels, George W. Bush’s first budget director, the RDA was a sign of the state’s serious intent in pushing for public-private funds to stimulate growth with projects like developing the airport, expanding commuter rail to serve a growth in residential expansion along the lakefront, and bringing high-tech businesses to the area.

A return-on-investment analysis published by the RDA stated that every $1 investment by RDA between 2006 and 2015 returned $5.21 cumulative economic output.

That’s great for the region, but not specifically for Gary, some activists say. Local participation in infrastructure rehabilitation is crucial because of “the local multiplier effect,” which posits that there is an economic benefit to an area from money being spent in the local economy. Gary suffers from the opposite.

“A dollar wakes up in Gary and goes to bed somewhere else,” Renee Hatcher told me.

The daughter of the former mayor is an IU graduate and earned her law degree from New York University. Hatcher is a clinical teaching fellow at the University of Baltimore School of Law specializing in community development.

Regional and state commissions fixate on the jewels, but these groups aren’t involved in the social problems, she said.

“It’s very much about who is in the room,” making these decisions.

Sometimes the room is absent of people who care about Gary’s residents.

Chicago/Gary International Airport is one of the highlighted assets in the 2014 Federal Reserve report.

For decades, state and federal officials have discussed the need for a third airport in the Chicago region to offset heavy traffic around O’Hare and Midway. Placing it in Gary should be logical choice, right?

The grounds are home to the Army National Guard and Boeing’s corporate fleet, but the airport has been a boondoggle. The last commercial fights were in 2013.

But there’s hope. In 2014, the airport commission, which has shifted from a city organization to a regional committee that includes Gary’s mayor, hired an outside vendor to take charge of the airport’s management, which includes provisions for 30 percent local participation.

Planned improvements, including resurfacing the airport’s apron, will make the airport more viable. Gary’s airport is touted as transportation hub, given its proximity to railways and highways.

In July 2015, Gary mayor Karen Freeman-Wilson, a hometown hero with a Harvard pedigree, celebrated the extension the airport’s runway to meet Federal Aviation Administration standards.

It took nine years to complete, at a final tab of $175 million — nearly twice the original estimate.

“From a labor perspective, we are very happy to get this done,” Dan Murchek, president of the Northwest Indiana Federation of Labor, told Northwest Indiana Times. “This opens the door and the potential for some good-paying jobs down the road.”

But runway construction didn’t include good-paying jobs for Gary residents, said Rev. John E. Jackson Sr., senior pastor at Gary’s Trinity United Church of Christ. He moved from Chicago to plant the church with the backing and support of his mentor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright.

Considering that construction jobs pay good wages, and major infrastructure projects like the airport use tax dollars, this should’ve been a boon for Gary’s residents, Jackson argued.

The project has minority-owned businesses quota, but there was not quota for hiring Gary workers. Data was not gathered on minority workers, but participation of residents as laborers was minuscule, according to Jackson and Ruth Needleman, a labor historian and professor emerita at Indiana University Northeast. Both are members of the Northwest Indiana Federation of Interfaith Organizations/Jobs Coalition.

“The work was done by people outside the community, and the workers come from Illinois and as far away as southern Michigan,” Jackson said.

Despite the need for jobs, activists such as the interfaith organization fought against the construction of a privately-owned 800-bed immigration detention facility.

Last May, the city council voted 9–0 to deny a request by Florida-based GEO Group for a zoning variance to build the prison next to the airport.

“This isn’t the kind of investment we need in Gary,” Needleman argued.

While RDA boasts a future of thousands of high-tech jobs, the major disconnect for Needleman and Jackson was the celebration by politicians and media for the construction of an immigration prison.

Consider the bile of seeing low-paid black people guarding brown people with profits going to the hands of white people in another state. But that wasn’t the only kick in the teeth.

Prior to the vote, GEO signed a memorandum promising to follow local workforce and contracting guidelines, “with a focus on developing a plan to engage local residents and companies in the construction phase of the project.”

Yet in the next sentence, GEO is promised it won’t be penalized if it could not meet local hiring goals.

“Even if they hire black contractors, that doesn’t mean that they’ll hire local black workers,” she says. “The only kind of sustainable investment is in people. We need on-going training, and not just for data entry or for hammer-and-nail jobs.”

It’s a familiar pattern — hope floats, reality deflates.

Riverboat gambling took off in 1996, with the Majestic Star I and II opening within months in the final quarter of the year. Today, the casinos are still open, but the company that owned them went bankrupt, and they’re pulling in revenue three-to-five times less per month than two casinos just west in Hammond, Ind.

President Donald Trump is still reviled by the city’s establishment for a perceived bait-and-switch over a casino development deal.

Hatcher wanted Gary to determine its own destiny. The antithesis is Unigov — a plan to push Gary into a countywide body that would dilute minority voices in decision making, said Hatcher and others.

It’s a plan that has picked up steam among regional and state officials as a solution for Gary. Hatcher is worried what Unigov would do to Gary.

“This would be the end of Gary,” he said after last March’s political debate. “Look at Indianapolis.”

A 2014 analysis on 40-year anniversary of Indianapolis’ Unigov highlighted the diluted political influence of minority voters with an expanded metropolitan region.

Major improvements to the region woke up a city once derisively known as “Naptown” — even leading the city to a successful Super Bowl week.

But the reawakening negatively impacted the black community, according to analysis by Jeff Wachter, an independent researcher in urban development.

One-in-three children in Marion County lives in poverty, mostly in the city and overwhelmingly black. African American political power is nil, wealth generation has been uneven at best, and gentrification is on the rise.

Hatcher’s fear is apt. Gary’s history is fraught with racial enmity and power grabs.

But maybe Gary’s free fall is about to break. Taking his first week in office as any indication, the new president is serious about infrastructure improvement across the country.

The creation of so many jobs could be good for Gary’s current residents, who are black, poor, and yearning for economic viability.

The only way for Gary to rise is if we get ourselves together.

This article originally appeared on Medium.