Written by Eileen Sepulveda with animations by Catherine Killough

Growing up, I lived in a community in which everyone and everything was forgotten. But I always wrote things down to remember.

Abandoned buildings served as playgrounds and junkyards were like treasure islands with no treasure. We lived in Moore Houses, a public housing project building in the Melrose section of the South Bronx. Moore Houses was named after Edward Robert Moore, one of the first board members of the New York City Housing Authority, better known as NYCHA. It was the 118th housing development to be opened by NYCHA. To date, NYCHA owns more than 2,000 buildings.

I was only a year old when my dad decided to move us from his one-bedroom apartment into a two-bedroom apartment in the projects. He also landed a job as a messenger at Goldman Sachs. My mother was a stay-at-home wife. Living in Moore Houses was like having an extended family. We had so many neighbors. Our next-door neighbor, a 60-year-old Puerto Rican, used to scream out loud about how hard his life was. Across the hall lived working-class families who either lost loved ones to drug addiction or gang violence. We were all exposed to the crack epidemic of the late 1980s. Crack swallowed folks up like quicksand.

They weren’t just my neighbors, they were my friends, and some did not make it out alive. As a community, we stuck together despite the challenges we faced growing up, and we all share some wonderful memories.

A Special, Lyrical Language Overcame Attempts to Silence My Voice

Now that I look back, my community has always influenced my career as a writer and journalist. I began writing poetry and keeping journals at a very young age. Having creative freedom was a great benefit for me. During my teenage years, my writing helped me dilute problems associated with poverty. My poetry reflected my rough upbringing in the concrete jungle of New York City. It wasn’t the fancy poetry you memorize in high school or the stuff I studied as part of my creative writing classes in college.

As a Latina, I was constantly reminded to keep quiet or keep my place. In my strict Puerto Rican household, I wasn’t able to talk about things like gender roles and identity, guns, drugs, and my coming of age as a woman of color.

When I found out my mom was reading my journal, I had to learn new ways to express myself, using words my mom didn’t and couldn’t understand. So my writing became lyrics to rap songs. I knew that for myself and many other kids growing up in the South Bronx, our writing and “rhyming,” as we called it, helped us discover a new voice, a new language. In response to the invasion of my privacy, I learned what some might call “the code of the streets.” I wrote and rapped about gunshots outside our bedroom windows as a by-product of violent gang wars.

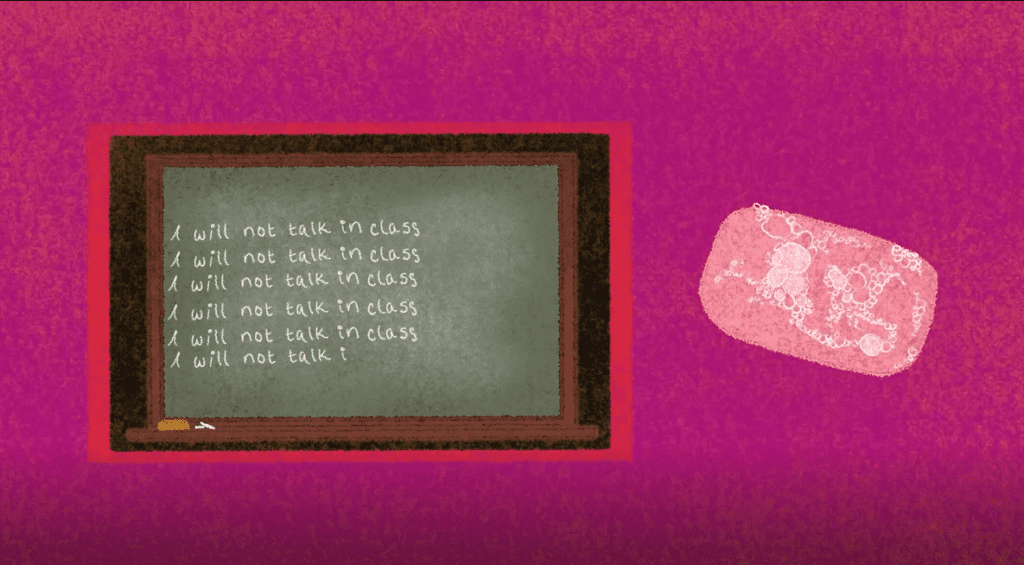

The silencing and putting me in my place also date back to elementary school when some of our teachers constantly told us to “be quiet” or threatened to wash our mouths out with soap for talking in class. They had us write “I promise not to talk in class” 100 times on the same green chalkboard on which we solved our math problems. I heard that “be quiet” admonishment a lot. I used to get called a chatterbox until I learned to sit there, fold my hands, and be quiet.

I remember Ms. Mullen wore dark red lipstick that stained her coffee mug. We saw cigarette butts in ashtrays with the same cherry red stains. She hated when we talked to each other, even when we had free time. She always kept a fresh bar of Ivory soap in the tiny sink in the back of the classroom. The bitter taste and smell of the soap lingered long after it had been washed away. When I made public appearances, spoke before crowds, or performed at school, I struggled to be confident and relaxed. Writing helped me with the fear of always being punished for using my voice.

Before I Was a Mom, I Was a Rapper

As a teen I found peace listening to rap artists like Run-D.M.C, LL Cool J, the Beastie Boys, and Public Enemy. Rap was about break-dancing moves, freestyling, and being the best lyrical artist outdoing competitors in rap battles. As the hip-hop rap culture evolved in the late 1990s, it took an unexpected turn. East Coast/West Coast rivalries emerged between Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls. During that era, I formed a group called 50/50 with a childhood friend. A high school classmate joined us and we formed Bronx Elementos (or Bronx Elements). It’s hard for me to recall how we came up with the names.

Before I became a mom, I was a rapper. It’s sometimes difficult for people to imagine me in that role, but it’s true.

During hot summer nights, while listening to beats on a boom box and with the fan on high in my bedroom, my friends and I rehearsed our song Seven Deadly Sins. The song title was inspired by a 1995 film starring Morgan Freeman and Brad Pitt. Unlike the movie, the song took you on a journey deep into the streets of the South Bronx where homicides and struggling single moms were our reality.

In March 1997, my friends and I were in the studio recording our first rap song for distribution to DJs and radio stations. I felt closer to my dream as I listened to the melody in the headset, as the drums and piano played and my words were recorded. It was already morning by the time we left the studio, so I put on my shades to block the bright sun rays. After completing our first track, we were exhausted but proud.

When we made it home from the studio, we turned on the radio and they were playing a marathon of Biggie Smalls hits. During one of the breaks, they announced he had been shot.

That same year we got to perform our song in a nightclub in the Bronx. I remember feeling nervous. It was one thing to rehearse in front of friends, but quite another thing to perform in front of dozens of strangers. Lights flashed across the electrifying dance floor as liquid smoke filled the air. The DJ played our tape of the studio-recorded track.

When you perform live, you feel like you’re in a completely different world. The experience is similar to the feeling of seeing your first article published.

But as far as my music career was considered, “It was all a dream,” as Biggie Smalls put it. Our group dissolved a year later, but we still remained very close friends. Around the same time, my father died, and I eventually moved out of the projects, as did my sister, brother, and mom a few years later. During the move, I lost all my journals and notebooks containing my poetry and raps. I also lost the only tape copy of our song.

From Hip Hop to Journalism

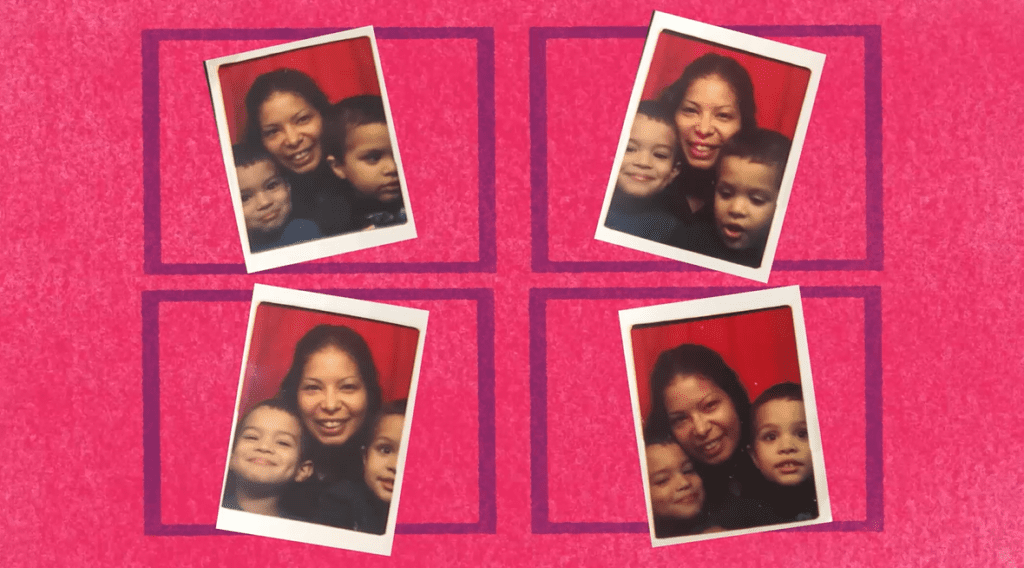

I went on to become the mother of my two wonderful sons, who are now 21 and 22. I earned a bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing as a single mom. My interest in journalism began during my junior year of college. I was encouraged to join the school newspaper after writing an article for my American Literature class. It discussed pop singer Rihanna’s song “American Oxygen” and how I believed it expressed the many struggles we face as people of color in America.

In time, I became editor-in-chief of the school paper and wrote pieces about the Bronx community’s struggles, including unfair policing, prison labor, and gentrification. I left my 9-5 to pursue a master’s degree in an attempt to expand my studies in journalism. Due to an unfair dismissal from my master’s program, I was unable to finish my degree. It was during this time that I met the wonderful people from Community Change who opened their doors and helped me through a very difficult time.

I now have the ability to write freely about these issues in spite of the fact that sometimes my words expose the harsh realities of living through poverty. I use that power today not only to tell my own story but also the stories of other people who experience the same struggles.

Spoken Word Reveals a “Beautifully Broken” Community

Brandon Leake grew up in the south side of Stockton, California, which he describes as a “beautifully broken” community. He is the first spoken word artist to win Season 15 of America’s Got Talent. His childhood, he says, “Was beautiful because of the people who were there” and broken because it was a food desert surrounded by “Liquor stores and drug stores around an overpoliced community.”

Brandon played basketball and hid his love for the spoken word because it was perceived as “soft” in his neighborhood. “I never really shared it with people until college,” said Brandon.

After winning, Brandon founded Called to Move. His organization works with youth, incorporating writing and literacy programs targeting issues like recidivism as early as third and fourth grade.

“You can never overcome people’s perceptions of who you are, what you’ll be, until you kinda take them there, so my art is my way of being able to take people to where I’m from,” he said. His team is piloting a new program in which a poet will be placed in the school district for a full year. “Where the need is, that’s where we’ll be,” he said.

By supporting and being supported by organizations like Community Change and Called to Move, we can continue healing. Although I didn’t make it as a rap artist, I realize that rap music and poetry provided me with the tools to continue my work not only as a journalist but as an economic justice advocate.