It’s fitting that James Robertson’s good luck falls during Black History Month.

Robertson, 56, started riding four buses and walking 21 miles round-trip to get from his Detroit home to his suburban factory job and back after his car broke down 10 years ago.

After Robertson’s story appeared in The Detroit Free Press on Feb. 4, his admirers donated more than $350,000 to a GoFundMe campaign. Last week, a dealership gave Robertson a new car.

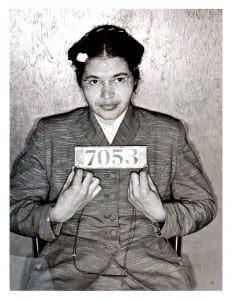

Rosa Parks, the mother of the civil rights movement, also called Detroit home in the years after her refusal to yield her seat to a white passenger sparked the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott.

Parks’ act of civil disobedience led to an overhaul of a racist and segregated transit system. Robertson’s story also lays bare how mass transit fails the riders who need it most, but it has a happy ending for him alone.

The other James Robertsons out there – people from the inner city who struggle to get to low-wage jobs in the suburbs – will not get crowd-funded campaigns or donated vehicles.

“Urban transit systems… have become a genuine civil rights issue – and a valid one – because the layout of rapid-transit systems determines the accessibility of jobs to the black community.”

That’s not recent critique from the head of the Detroit NAACP or even a progressive city council member blasting the region’s two poorly funded and poorly connected transit systems – one for the city and another for the suburbs.

Those are the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in “A Testament of Hope,” an essay published posthumously in 1969.

“If transportation systems in American cities could be laid out so as to provide an opportunity for poor people to get meaningful employment, then they could begin to move into the mainstream of American life,” King said.

People getting by on lower incomes tend to spend more time and money getting to and from work and are more likely to rely on public transportation. It’s only fair that mass transit works best for those who need it most.

Detroit regional transit officials have acknowledged the spatial mismatch between where people work and where they live.

They’ve also acknowledged that no fix is likely; the political will just isn’t there.

Instead of real reform that would make it easier for people to provide for their families, we get feel-good stories circulated on social media.

The initial news story about Robertson was shared on Facebook more than 136,000 times, with over 13,000 people worldwide donating money to the GoFundMe campaign.

But another story that urged readers to ask suburban towns to opt into the regional bus service that serves riders like Robertson was shared just 1,355 times.

Robertson earns just $10.55 an hour, not enough to get a car after his conked out 10 years ago. His is a struggle common to thousands of Americans who work low-wage jobs across the country.

What they need is bus routes that make the commute from the cities to the suburbs quick and affordable. Those Americans need cooperation between the suburbs and the cities so that people without cars aren’t shut out of suburban jobs.

But examining all the barriers that make it hard for people to make ends meet is hard work.

While our collective effort to improve mass transit will pay off in the end, it won’t give you that instant warm fuzzy feeling donors get when they give a few dollars to a man who has worked incredibly hard to keep his job.

Here the words of King are instructive: “Philanthropy is commendable, but it must not cause the philanthropist to overlook the circumstances of economic injustice which make philanthropy necessary.”

What we need now is not click-through generosity for individuals like Robertson, but a transformation of metro Detroit’s bus system and systems just like it in urban centers across the country.

If we pay attention not just to Robertson’s story, but also to the broken transit system that made it possible, his trek could be the start of a movement for those on the margins not just because of their race, but because they’re living on the brink.

Black History Month isn’t just an occasion for solemn reflection; it’s an opportunity to use the movement’s lessons to build a better future for us all.

Applying the band-aide solution of giving a car to a man whose problems stem from a transit system, an employer and a government that have all failed him would be akin to demanding a reserved bus seat for Rosa Parks and calling it a day.

But Rosa Parks’ story didn’t end on the day of her arrest. It was followed by the refusal of 40,000 black commuters to use Montgomery buses for the next 381 days, ending ultimately in the desegregation of the transit system.

James Robertson’s doesn’t have to either.

Featured image via Esben Bøg Jensen.