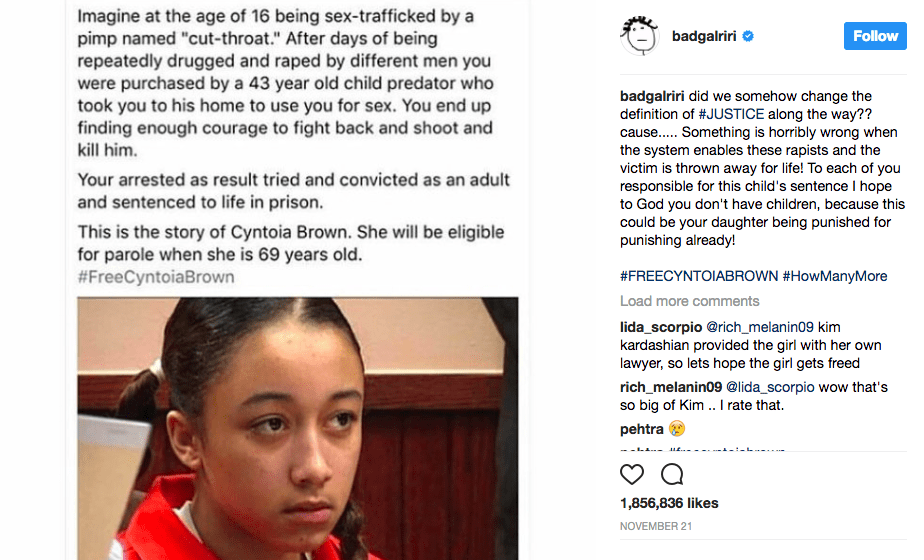

In the whirlwind of news about men taking advantage of underage girls and male abuses of power in Hollywood, politics and beyond, the Cyntoia Brown case went viral 13 years after she was sentenced to life in prison, following this Instagram post by Rihanna:

In 2004, Brown was convicted of first-degree murder after fatally shooting Johnny Mitchell Allen, a 43-year-old Nashville real estate agent who solicited sex from her when she was 16. News stories have focused primarily on the plight of an unfortunate girl subjected to years of sex trafficking and other abuses, finally confronting and killing an abuser but nevertheless sentenced to life in prison for murder.

The redemptive and sexual abuse issues surrounding the case warrant attention, but Brown’s fate also reveals significant problems with Tennessee’s juvenile justice system. Specifically, the case of Cyntoia Brown highlights the need for Tennessee legislators to lift mandatory minimums for convicted juveniles and recognize youth have no place in the adult system, regardless of the offense.

People nationwide are mortified by Brown’s sentencing, including celebrities like Kim Kardashian, who lent her legal team to this cause. Understanding state law helps explain how we — and Cyntoia Brown — got here and what needs to happen next.

Tennessee’s 51-to-Life law

Although Brown was sentenced to life with the possibility of parole (at age 67) for killing a man who solicited sex from her as a minor, this is, indeed, the most lenient sentence possible under Tennessee law.

Under state law, only three sentencing options exist for those convicted of first-degree murder, no matter the age of the accused: death penalty, life in prison without possibility of parole and prison with the possibility for parole after serving 51 years.

The United States Supreme Court has ruled that sentencing a minor to death or a life sentence without the possibility of parole is unconstitutional cruel and unusual punishment. A separate Tennessee law also forbids imposing a death sentence on minors tried as adults.

Hence, the minimum sentence for a minor’s first-degree murder in Tennessee is a life sentence with the possibility of parole after 51 years.

Tennessee’s 51-to-Life law may not even be constitutional when applied to minor cases. In 2012, in Miller v. Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a mandatory life sentence without the possibility of parole violates the U.S. Constitution’s eighth amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Youth advocates take the position that a mandatory 51-year sentence without parole is actually a life sentence because the average life expectancy in prison is about 50 years.

Unfortunately for Brown, the Tennessee Criminal Court of Appeals has disagreed and maintains the law is constitutional. Currently, about 183 individuals are serving a life sentence for crimes committed as minors.

The difference between youth and adults

The juvenile justice system was created based on the reality that youth do not have the mental capacity to fully appreciate wrongs. Since the Miller case, at least one state’s highest court, Iowa, has held even short mandatory sentences for juveniles are unconstitutional, stating, “mandatory minimum sentences for juveniles are simply too punitive for what we know about juveniles.”

In recent years, the Supreme Court has heavily relied on neurological and social science research indicating the developing minds of youth make them less culpable than adults.

For example, the Miller court leaned on guidance from the American Psychology Association, which concludes “youth are particularly prone to engage in and are vulnerable to high-risk situations” because “the part of a youth’s brain responsible for judgment and impulse control does not communicate in balance as an adult’s would, and therefore does not give juveniles the same degree of control over their behavior.”

The problem with Tennessee

The Cyntoia Brown case reveals problems with how Tennessee sentences youth exposed to childhood trauma when facing a first-degree murder conviction.

In Miller v. Alabama, the Supreme Court urges that individual mitigating factors must be taken into account when sentencing young people. Specifically, the court notes several factors to consider in youth sentencing, including the youth’s history of family violence, parental substance abuse, child abuse and mental health issues.

Unfortunately, the Miller Court’s 2012 mandate to consider childhood trauma as mitigating factors came too late to help 16-year-old Brown, originally sentenced in 2004. Brown’s jury did not get to hear information about how the girl was placed for adoption by her mother — only to be later kidnapped by her mother and sex trafficked. The jury also did not get to learn Brown showed signs of fetal alcohol syndrome because her mother drank heavily while she was pregnant.

Of her former pimp “Kutthroat,” Brown told an appeals court judge: “He would explain to me that some people were born whores, and that I was one, and I was a slut, and nobody’d want me but him, and the best thing I could do was just learn to be a good whore,” according to Newsweek.

Just like Brown, youth appearing in the juvenile and adult systems likely have exposure to a number of childhood traumas. According to a 2012 Sentencing Project survey of people sentenced to life in prison as juveniles, 79 percent witnessed violence in their homes regularly, and fewer than half attended school at the time of their offense. Of women handed life sentences as minors, 80 percent reported histories of physical abuse, and 77 percent reported histories of sexual abuse.

Yet, children exposed to childhood trauma fare no better today in Tennessee adult courts under the still-existing 51-to-Life law. The life sentence is mandatory in Tennessee first-degree murder cases, regardless of the accused minor’s age and traumatic experiences.

The enormous cost of housing youth offenders for life is also troubling under the state’s mandatory 51-to-Life law. According to an American Civil Liberties Union study, a 50-year sentence for a 16-year old costs about $2.25 million in public money to imprison one individual, based on national averages.

In Tennessee, where it costs roughly $27,000 to house a prisoner annually, individuals serving life sentences for convictions as minors cost taxpayers more than $4.9 million each year.

Tennessee’s 51-to-Life law also does not take into account the power of rehabilitation, and the fact minors who have made serious life-altering mistakes can change.

Despite bipartisan efforts and heavy support from youth justices advocates, legislative attempts that would let youth see parole possibility sooner have repeatedly failed. A measure supported by State Reps. Mike Stewart (D-District 52), Mark White (R-District 83) and Brenda Gilmore (D-District 54) that would make individuals convicted to life sentences as minors eligible for parole after serving 25 years failed in the 2016 legislative session.

In another legislative attempt in early 2017 a similar bill pushed by State Rep. Gerald McCormick (R-District 26) and State Sen. Doug Overby (R-District 2) that would make lifers convicted as teens eligible for parole after 20 years, also failed.

Minors on the move to adult courts

Cyntoia Brown’s case also highlights problems with Tennessee’s stance on transferring minors to adult criminal courts.

Minors who commit serious crimes such as murder are deemed beyond the rehabilitative resources of Tennessee juvenile courts. Thus, youth accused of crimes such as first-degree murder are transferred to the adult system, regardless of the youth’s traumatic upbringing or circumstances.

There is no minimum age for transfer of a minor in Tennessee for serious charges such as murder, rape or kidnapping. Youth as young as 14 are regularly transferred to adult courts under Tennessee law despite research showing adolescent brains are not as fully developed as adults.

Tennessee is not alone in this regard. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, Alaska, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina and West Virginia also have no minimum age for adult prosecution of children.

Under Tennessee transfer law, factors considered by juvenile courts in deciding whether to transfer youth to adult court do not include a young person’s exposure to childhood trauma.

Youth justice advocates argue that youth who experience trauma, like Brown, need rehabilitative services and protections supposedly afforded by juvenile courts the most.

Race and poverty also play a big part in youth outcomes. The transfer of juveniles to adult court is disparately impacted by race and poverty, with youth of color transferred at the highest rates. Young people of color are also more likely to face a life sentence because of the higher frequency of transfers to adult court.

Going beyond justice for Brown, now 29, seems necessary. Youth advocates are hopeful the Tennessee General Assembly will use the resurface of the Brown case to right some of the many quite obvious wrongs of the Tennessee juvenile system.

Demetria Frank is an assistant professor of law at the University of Memphis Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law. She teaches courses in evidence, federal courts and mass incarceration.

This article first appeared on MLK50: Justice Through Journalism.